The Death of a Samurai

Talk the Talk

It literally means Stomach Cutting or Self-Disembowelment and is also known by the more colloquial expression Hara-kiri, which can be said to translate to the more vulgar term, Gutted.

Walk the Walk

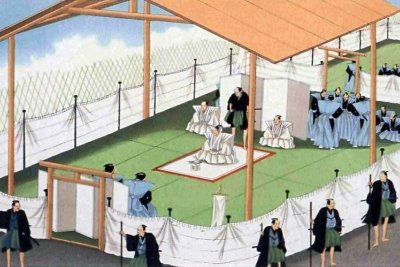

First, they had to get permission for revenge from the local authorities by issuing a letter detailing why the act was needed.

How the opponent was to be killed was of no consequence, but there could be no public disorder as a result of the ensuing violence.

Ideally, revenge had to be carried out by the next of kin but if this was not possible, then the responsibility would go to other clan members.

When the antagonist was dead, those that served the revenge would then hand themselves into the nearest authorities and once they proved that the killing had prior authorisation, they would be free.

This practice continued until, in 1873, an imperial decree was issued outlawing the practice as a part of the ongoing modernisation of Japan.

Samurai Quote

~ Daidoji Yuzan ~

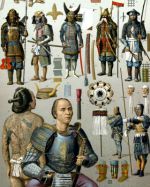

For the samurai, one of the most important things was his honour and so ingrained in his psyche was the idea of protecting it, he was even willing to die in order to keep it. Ideally, the death of a samurai would come in battle against a famous warrior after a great fight that people would tell stories about for generations. If this could not be the case however then as long as he died serving his lord, his honour would be intact.

For the samurai, one of the most important things was his honour and so ingrained in his psyche was the idea of protecting it, he was even willing to die in order to keep it. Ideally, the death of a samurai would come in battle against a famous warrior after a great fight that people would tell stories about for generations. If this could not be the case however then as long as he died serving his lord, his honour would be intact.Overcoming the Fear of Death

The Hagakure (Hidden Leaves) was a spiritual guide for the samurai written by Yamamoto Tsu-Zmoto in the early eighteenth century, it stated that Bushido (the Way of the Warrior) was to be found in death.It was believed that the fear of dying should be mastered by a samurai warrior as otherwise it may impede his ability to serve his feudal Lord and as he was expected to do this in this life and the next, then fear itself was an exercise in futility.

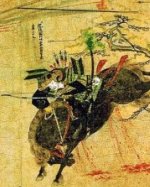

Musha Shugyo and Duelling

The most talented swordsmen would go on musha shugyo, a form of pilgrimage that would take them around the country to challenge the best fighters they could find to a duel. These were not usually officially fights to the death but to die in defeat was far from uncommon. If a combatant did happen to be defeated and survive, he would often become a loyal student to the master who beat him but to a swordsman with a school of his own, losing a fight could mean ruin as he would lose his students, and therefore his income.During a duel, both participants were expected to act with honour and obey the local Bushido code, however, this did not always happen. When a young Tsukahara Bokuden defeated the more experienced Ochiai Torazaemon and let him live, revenge was on the older man’s mind. Torazaemon laid in wait and ambushed Bokuden but his treachery ended in a dishonourable death and set the younger man on a path to becoming one of the most respected samurai that ever lived.

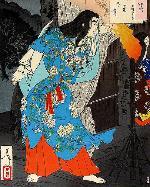

Conversely, sometimes focusing too much on proper etiquette could get you killed, as was the case in the duel between Miyamoto Musashi and Sasaki Kojiro while the former was on his musha shugyo. When Musashi arrived, he was late, was dressed like a tramp and had a wooden sword he had fashioned out of an oar on the way to the fight. This enraged Kojiro, (who was considered the best swordsman and the finest samurai warrior in the whole of Japan at the time) and as fighting with no emotion is always preferable to fighting in anger, this probably contributed to his defeat and subsequent death (depicted above).

Seppuku – An Honourable Suicide

If a samurai’s honour or loyalty were compromised, he would be put to death and his heir and sometimes his whole clan could lose any land and social status that had previously been granted. One way to lose your honour was to suffer a crushing defeat in battle and rather than return home in this manner or be taken captive, many would commit seppuku.By the thirteenth century, the tradition of seppuku was well established and was specifically introduced as a way to save or regain honour as the level of pain involved demonstrated a willingness to face death head-on. In later years however, it was modified and made slightly less painful as a second, known as a kaishaku, was used to decapitate the samurai after he cut himself open with his short samurai sword (known as a wakizashi ).

Lord Redesdale, a young British diplomat in Japan, witnessed the death of a samurai who he saw commit seppuku in the 1860s and gave a vivid description of the act, stating;

Carefully, according to custom, he tucked his sleeves under his knees to prevent himself from falling backwards; for a noble Japanese gentleman should die falling forwards. Deliberately, with a steady hand, he took the dirk [short sword] that lay before him; he looked at it wistfully, almost affectionately; for a moment he seemed to collect his thoughts for the last time, and then stabbing himself deeply below the waist on the left-hand side, he drew the dirk slowly across to the right side, and, turning it in the wound, gave a slight cut upwards.

During this sickeningly painful operation, he never moved a muscle of his face. When he drew out the dirk, he leaned forward and stretched out his neck; an expression of pain for the first time crossed his face, but he uttered no sound. At that moment the kaishaku, who, still crouching by his side, had been keenly watching his every movement, sprang to his feet, poised his sword for a second in the air; there was a flash, a heavy, ugly thud, a crashing fall; with one blow the head had been severed from the body.....

Further Reading:

Cook, H. 1993. Samurai – The Story of a Warrior Tradition. London. Blandford Press.Death and the Samurai. [Internet]. 2013. Samurai Archives. Available from: http://www.samurai-archives.com/death.html [Accessed July 8, 2013].

McIntyre, K.J. 2000. [Video Documentary]. Soul of the Samurai. Live Art Television. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YbFPlAHW0nU [Accessed May 21, 2013].

Newman, J. 1989. Bushido – The Way of the Warrior. New York. Gallery Books

Renius, A. [Internet]. 2008. A Comparison of the Concepts of Honour Held by the Samurai of Japan and European Knights. Socyberty.com. Available from: http://socyberty.com/history/a-comparison-of-the-concepts-of-honour-held-by-the-samurai-of-japan-and-european-knights [Accessed July 8, 2013].

Seppuku. [Internet]. 2008. Reference.com. Available from: http://www.reference.com/browse/seppuku [Accessed July 8, 2013].

Turnbull, S. R. 1987. Fourth Edition. Samurai – A Military History. London. Osprey.

More Samurai History

A brief overview of the history of the samurai, looking at the rise and development of the leading social class in Japan and some of the cultural traits than made the samurai warriors unique such as their weapons and their code of ethics, known as bushido.

The Heian Period was a time of major change in Japan as it saw the rise of a new warrior elite, the Samurai. The leaders of this new power would dominate the politics of the country for centuries and would even supplant the power of the Emperor, though not without a struggle.

Tomoe Gozen is a rare example of a female Samurai warrior and is believed to have been involved in the Gempei wars (1180 – 1185). She fought alongside her Master, Minamoto Yoshinaka, though it is unclear how much of her story is actually true.

The tragic tale of samurai legend Yoshitsune Minamoto. After helping his brother Yoritomo win the Genpei War and gain control of Japan, he was denied the titles and rewards he should have received for his services and was ultimately hunted down as a traitor.

A look at the change and turmoil experienced by the ruling elite of Japan during the Kamakura Period and the Kemmu Restoration. A series of civil wars and two invasions from the Mongols saw powershifts not only between rival families, but also between the titles of the Emperor, the Shogun and the Regent.

While the samurai warriors of the late thirteenth century were formidable warriors in their own right, when faced with the onslaught of the Mongol Hordes they seemed to be fated to lose. They were outclassed in every way by however things did not go according to plan for the foreign invaders.

The samurai sword, it is said, was believed to contain the soul of the warrior who owned it. While this is probably an over romanticised view, it is true to say that there was a spiritual connection not only for the wielder of the katana, but also for the sword smith and his creation.

Tsukahara Bokuden was a samurai warrior who lived in the 16th century. In his early days he exemplified what a samurai should be and was known as one of the fiercest warriors around. However in later life, Bokuden would take on a more pacifist philosophical stand point.

The main business of the samurai was war and while tactics and weapons changed through the years, the willingness to die for their lord was a constant. In return, they could gain riches and status, as well as the best of them gaining a kind of immortality by having stories told about them for centuries to come.

The images on this site are believed to be in the public domain, however, if any mistakes have been made and your copyright or intellectual rights have been breeched, please contact andrew@articlesonhistory.com.

.jpg?timestamp=1581079761328)

thumb.jpg?timestamp=1581080970224)