The Roman Republic

Talk the Talk

The word Republic is derived from the Latin phrase Res Publica, which can be translated as Public Affair or Property of the People.

Despite this, the Roman Senate was mostly made up of aristocrats (the patricians) and much of the Roman Republic era saw political wrangling known as the

Conflict of Orders which was intended to get representation in government for the lower social classes (the plebeians).

Walk the Walk

Lucius Junius Brutus was a semi-legendary figure who is said to have brought about the start of the Roman Republic era when he dethroned the last king of Rome, Tarquinius

Superbus (R. 535-509 BCE).

He became one of the first consuls of Rome in c.509 BCE and is credited with founding many of the basic institutions that began in the early

Republic era.

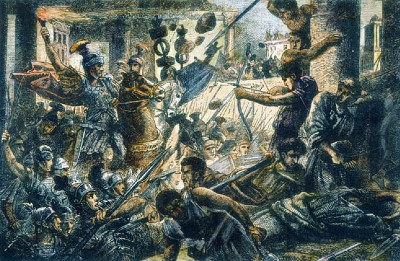

According to some sources, he executed two of his sons for plotting the restoration of Tarquinius and Brutus met his own demise at the hands of his cousin

Arruns Tarquinius, the second son of the usurped king, when they fought in single combat during the Battle of Silva Arsia and simultaneously speared each other to death

(depicted above).

Despite this, the Romans managed to stave off Tarquinius’ attempts to regain his throne and after a hard-fought battle, the king’s Etruscan soldiers were

forced to flee the battlefield.

From its conception in around the eighth century BCE, Rome was ruled by a series of kings until in c.509 BCE, the tyrant king Tarquinius Superbus was ousted from the throne by his nephew Lucius Junius Brutus and sent into exile.

This brought about the end of the Period of Kings and transformed the ancient Roman city-state, still relatively small at this time, into a Republic. This period can be divided into three stages, the early Republic (c.509 – 290 BCE), the mid Republic (c.290 – 88 BCE) and the late Republic (c.88 – 31 BCE).

Politics in the Early–Mid Roman Republic

Power was now mainly in the hands of two consuls and to a lesser extent other magistrates who performed a variety of responsibilities within society.

The consuls were elected annually in order to prevent any one man or group gaining too much power as the kings had done previously. They acted as civic rulers in times of peace and in times of conflict, they were charged with being commanders in chief of the Roman army.

They were drawn from and voted for by the Senate which consisted of around three hundred members of the patrician class who were the ruling elite, made up of representatives of the oldest and wealthiest families in Rome.

This did not sit well with many people from the lower orders (plebeians) and so the early–mid Republic Period was marred with social strife known as the Conflict of Orders.

As a direct result of these problems a written law code known as The Twelve Tables emerged in 449 BCE. This laid out the basic rights and duties of all Roman citizens and acted as a foundation for future laws that accumulated during the Roman Period and beyond.

Over time the common people did gain some representation through tribunes who could initiate or veto legislation. However, by around 300 BCE the only plebeian representation in the Senate was from families who had amassed considerable wealth and were therefore just as powerful and arguably as detached from the masses as their patrician counterparts.

The Senate had existed during the Period of Kings as an advisory council to the ruling monarch and continued in a similar role for the various executive magistrates going into the early Republic. By the middle Republic, its powers had grown considerably though would diminish substantially by the end of the late Republic era.

The Roman Army During the Republic Era

In the early Republic, the Roman army was made up of a local militia who would take up arms when required. As they had to provide their own equipment they were usually drawn from the richer families and though poorer soldiers could make up some of the armed forces, those with money and therefore better armour and weapons would make far more effective fighting men. The main body of the Roman army were infantrymen who would go into battle using hoplite tactics, whereby they organised into groups (phalanxes) that fought in tight formations.

By the time of the mid-Republic, they were organised into legions which were divided into thirty smaller groups called manipulus (literally a handful) that consisted of between sixty to one hundred and twenty men. Most well-equipped soldiers would have a short stabbing sword called a gladius, a javelin known as a pilum and would be protected by an oval shield.

The manipulus would organise into three battle lines that were more flexible than the earlier phalanxes. They would be arranged with the younger soldiers known as the hastati at the front, the second line would contain more experienced and well-equipped men known as the principes and the rear would contain the triarii, battle-hardened veterans and usually the wealthier of the three groups.

Cavalry units known as equites were also utilised and would help protect the flanks of the infantry on the battlefield. These were higher paid than the infantrymen and at this time had to provide their own horse so would tend to be from wealthy backgrounds but by around the second century BCE, they would largely be replaced by auxiliary troops.

Up until the second century BCE, the Roman army would also contain a skirmishing unit known as the velites. These were usually young and poor so had little in the way of armour and mainly fought with a gladius, a throwing spear called a veles and a small round shield called a parma.

In 107 BCE, it was realised that a professional army with full-time soldiers was needed to replace the existing civilian militia as a reaction to the growing territory that needed to be protected, maintained and expanded upon. Reforms to this end, known as the Marian Reforms, were instigated by Gaius Marius and soldiers would now sign up for duty for twenty-five years.

All equipment would be standardised and provided by the state and soldiers would spend much of their time training and perfecting battle tactics.

As the period progressed, many rich people acquired increasing amounts of farmland and as more territories were conquered, more and more slaves were brought to the Italian peninsular, often working the land. This would have allowed a higher number of young men to become full-time soldiers than would have previously been possible as with slaves working the land, fewer Roman citizens needed to be involved in food production.

The Expansion of the Roman Republic

The ancient Romans developed their territory and expanded as the nation came into conflict with, and defeated other city-states, kingdoms and empires who were either a threat or considered easy to conquer by ambitious magistrates. When a new political area did come under Roman control, they were allowed to maintain their culture and by and large their political institutions. Often their leaders would be made governors of the country or district giving them considerable power when dealing with local issues, though leaving them still answerable to Rome.

Conquering other nations was a driving force in the growth of Rome for several reasons besides just acquiring new lands. These include controlling trade lines and products in and out of the newly gained territories and loot in the form of food, precious metals and slaves that were all taken back to Rome.

Once a new area was defeated, its people were often extended some form of citizenship which was also instrumental in the growth of Rome in the Republic era as they would send taxes to the capital and were often required to provide soldiers to bulk up the Roman army in the form of auxiliary units.

In order to connect these new territories, the Romans began building roads across their sphere of influence which made the movement of goods and soldiers easier and more efficient. Successful military campaigns could also provide funds for other building projects, for example, victorious generals would often use some of the wealth they plundered on campaigns to build temples which they would dedicate to one of the gods.

In 211 BCE, a small coin called the denarius was introduced and this became a standard unit of currency for centuries to come. This made the exchange of goods and services across an ever-increasing area much easier meaning it also made a major contribution to the expansion and growing affluence of Rome.

The End of the Roman Republic

In the first century BCE, Rome saw a period of chaos leading to civil war in 88 BCE when General Lucius Cornelius Sulla marched his forces on Rome itself and defeated his rival, the man who had earlier reformed the military, Gaius Marius. Soon after, there was more unrest in the country when Marius reclaimed the city while his nemesis was away on campaign but Sulla soon returned, retook Rome at the Battle of the Colline Gate (depicted below) and declared himself dictator, a position he would hold from 82 - 79 BCE in an attempt to stabilise the state.

This ongoing unrest and upheaval weakened the foundations of the Roman Republic and this deterioration only grew stronger in the coming decades, especially when Julius Caesar rose to power in 60 BCE (though he would never actually become an emperor and the nation technically remained a Republic).

When he conquered Gaul (modern-day France) in 51 BCE, his power and popularity grew and this was followed by his victory in his civil war with the Senate, led by his former friend and ally Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great).

Caesar declared himself dictator for life in 44 BCE however, this angered many of the ruling elite and Senate members as it was believed he was becoming a 'king in all but name' and as a result, he was assassinated in the same year.

This led to another series of civil wars that ultimately saw Caesar’s great nephew and heir Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (Octavian) became the unchallenged sole ruler of Rome. He assumed the title of Augustus and became the first official Emperor of Rome soon after, bringing an end to the Roman Republic after five hundred years and ushering in the era of Imperial rule known as the Principate Period.

Written by Andrew Griffiths – Last updated 30/07/2025. If you like

what you see, consider following the History of Fighting on social media.

Further Reading:

Ancient Rome. [Internet]. 2020. History.com. Available From:

https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/ancient-rome

[Accessed Jan 15, 2021].

Lucius Junius Brutus. [Internet]. 2020. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available From:

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Lucius-Junius-Brutus-legendary-Roman

[Accessed Jan 15, 2021].

The Organization of the Roman Army. [Internet]. 2021. Penn State University. Available From:

https://sites.psu.edu/successoftheromans/organization-of-the-roman-army

[Accessed Jan 15, 2021].

The Rise of Rome. [Internet]. 2021. Penn State University. Available From: https://sites.psu.edu/successoftheromans/the-rise-of-rome

[Accessed Jan 15, 2021].

The Roman Empire: A Brief History. [Internet]. 2019. Milwaukee Public Museum. Available From:

https://www.mpm.edu/research-collections/anthropology/anthropology-collections-research/mediterranean-oil-lamps/roman-empire-brief-history

[Accessed Jan 15, 2021].

The Roman Republic. [Internet]. 2018. Khan Academy. Available From: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/world-history/ancient-medieval/roman-empire/a/roman-republic

[Accessed Jan 15, 2021].

Your Guide to the Roman Republic. [Internet]. 2020. History Extra. Available From:

https://www.historyextra.com/period/roman/roman-republic-guide-how-senate-plebeians-citizenship-women-democratic-fall-end

[Accessed Jan 15, 2021].

More Roman History

Roman Army History Home

A look at the weapons, tactics and organisation of the armies of ancient Rome and how they evolved from a small civil militia in the seventh century BCE in to the most formidable fighting force in the known world by the first century BCE and eventually saw the fall of the Roman Empire by the fifth century CE.

A look at the weapons, tactics and organisation of the armies of ancient Rome and how they evolved from a small civil militia in the seventh century BCE in to the most formidable fighting force in the known world by the first century BCE and eventually saw the fall of the Roman Empire by the fifth century CE.

The Period of Kings in Ancient Rome

A look at the early history of ancient Rome, commonly known as the Period of Kings. While much of this period in Rome’s history is steeped in myth and legend, it is clear that it began to expand soon after its conception. Its population and territories grew under a series of kings who worked in tandem with an elected senate.

The Enemies of Rome in the Early Republic

The Early Republic (c.500 BCE – c.290 BCE) was a time of unremitting conflict for Rome and was characterised by wars, battles and skirmishes with the many tribes and states that surrounded them. This continued for over 200 years until the end of the Third Samnite War, by which time most of the Italian Peninsula came under the sphere of influence of the Roman Republic.

The images on this site are believed to be in the public domain, however, if any mistakes have been made and your copyright or intellectual rights have been breeched, please contact andrew@articlesonhistory.com.